Russian Disinformation Campaigns and the Role of Strategic Communications in Planning Successful Foreign Policy

Mariam Orjonikidze

Abstract

The aim of the article is to outline the essence and role that the strategic communications play for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia. The paper emphasizes challenges faced by the Strategic Communications Department of the Ministry. For further clarity, the article focuses on combatting Russian disinformation.

The term “Strategic Communications” gained particular popularity towards the second decade of the 21st century. In a wider sense, strategic communication entails a sequence of events/occurrences that provides for the informational environment that is capable of changing or strengthening the consensus that exists within the broader public or particular groups. The term is interchangeably used with “Targeted Communications”. Its purpose is to bring to the fore the strategic goals of the state or an organization.1 Usually strategic communications help the implementation of the strategic goals of the state or an organization, and stresses the importance of communication in achieving the strategic interests and goals.

According to the Foreign Policy Strategy of Georgia 2019-2022, the accession to the EU and NATO is among the top priorities of Georgia, along with strengthening strategic partnership with the United States and establishing close cooperation with European states. Positioning Georgia in a favourable light on the international arena is also a national goal. Thus, through communicating outside the country, the Strategic Communications Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia supports Georgia’s diplomatic missions abroad in terms of achieving the aforementioned goals. Despite the overwhelming support for the Western foreign policy vector among the public, Georgia’s foreign policy priorities face several pressing challenges, chief among them being disinformation, which represents a threat to the state both internally and externally.

The multifaceted concept of strategic communications is helpful in terms of both the attainment of a nation’s strategic goals as well as being on the front line. That is, it focuses on the identification and containment of foreign threats that interfere with the implementation of Georgia’s strategic goals. Therefore, one of the communication goals of the Government of Georgia is to prevent and decrease anti-Western propaganda, both internally and abroad.

The goal of the paper is to determine the significance of strategic communications for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in terms of anti-Western/Russian disinformation. The article attempts to illustrate to the reader that, when observed correctly, Russian disinformation narratives may actually give away the Kremlin’s intentions, allowing other actors to take pre-emptive measures.

A new stage of Russia’s information war against Georgia began in 2002, after the former President Eduard Shevardnadze commenced active cooperation with NATO.2 After the Rose Revolution and the plebiscite held in 2008, showing overwhelming support among Georgians for joining NATO (above 70%), the information war became an auxiliary dimension of Russia’s military efforts.3 Despite the 2008 military confrontation, the post-bellum period was characterized by ever tighter cooperation with the EU and NATO. In 2014 Georgia signed the Association Agreement with the EU, along with the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area Agreement.4 Additionally, Georgian citizens were granted visa-free travel to the Schengen Area in 2017.5 In this regard, Russia aims to disrupt Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration by decreasing cooperation between Georgia and Western institutions.

Russian disinformation campaign goes beyond mere propaganda to encompass a long-term practice of usage of information as a weapon. Reflexive control is a rather significant component of Russian disinformation, demoralizing and paralyzing the adversary.6 Often Russia resorts to an old Soviet method known as ‘Active Measures’, the practice of conjuring up fictitious events/happenings.7 Russia’s information campaigns are coordinated at the highest levels of its government.8 It is noteworthy that Russia’s ‘active measures’, coupled with other methods, are integrally intertwined with the Kremlin’s foreign policy and military goals.9

Georgia became a target of Russia’s continuous disinformation campaigns after consolidating integratory processes with the West.10 Considering the imbalance of power between Georgia and Russia when it comes to information wars, conducting strategic communications serves as an important containing instrument in combating Russia’s disinformation.

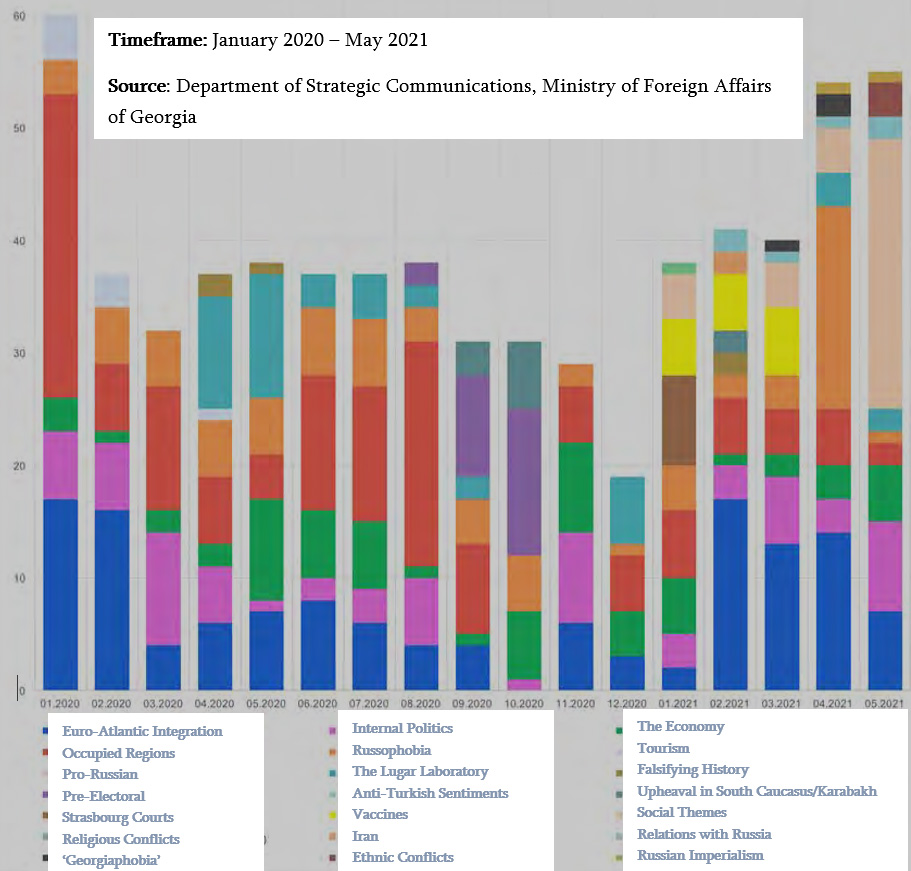

Within the wider framework of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Department of Strategic Communications conducts monitoring and analysis of Russian-language media. The statistical method employed by the department outlines and tallies informational activity in terms of keywords. This method is used to determine the most relevant and actively disseminated issue within a given timeframe.

Often articles containing disinformation only use one sentence of phrase to disseminate the pre-selected message, with the rest of the article acting as a cover, thus, influencing the reader. Data analysis revealed that issues like European and Euro-Atlantic integration, as well as those related to occupied territories remain continuously relevant. The ‘Russophobia’ narrative is also actively reproduced. Nevertheless, along with current events, new narratives also emerge, such as: the Coronavirus and Vaccination,11 the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the economy, etc. The presence of disinformation across said dimensions is also confirmed by the Disinformation Review published by the EU.12

From December of 2020 to May of 2021 the Department of Strategic Communications collected 722 articles in its database, approximately 40 articles per month. Each article is coded with a keyword, which expresses the contents of the article, for example: anti-Turkish sentiments, occupied regions, etc. Articles are collected using search systems/engines. The graph below illustrates various thematic issues in use of the Russian media regarding Georgia.

Based on statistical data analysis, an overarching pattern of Russian disinformation becomes clear: preparatory manipulation of public opinion and, subsequent, publication of an official disinformation narrative in line with the preparatory work. This is done in order to advance Russia’s foreign policy goals. Therefore, delving into the contents of a publication that appears in the Russian media could enable the identification of the Kremlin’s narrative and its potential next steps vis-à-vis Georgia and the wider region.

According to the analysis of the outlined timeframe, three key disinformation narratives were identified for Georgia: ‘Russophobia’, biological security, and tensions in the South Caucasus. The origins of the said narratives and their practical application are discussed below in a greater detail.

Russophobia, the June 2019 Protests and Pozner’s Visit

Construction of ‘russophobic’ narratives became an integral part of Russian disinformation. This method is used for the purposes of discrediting one’s opponent, as well as to mask failure. According to the aforementioned data set, the issue has always been at the forefront of Russian disinformation, with sporadic patches of heightened frequency, like during the 2019 June protests and recent arrival of the Russian journalist Vladimir Pozner Jr. Both cases were used to corroborate the existing narrative that Georgia is a ‘russophobic’ country. Additionally, the 2019 June protests became an excuse for Russia to exert an economic pressure on Georgia. Russia media underscores that the raging ‘Russophobia’ in Georgia has made it impossible to reinstate direct flights between the two countries.13 The issue reached a new mark in 2021 after the arrival of the Russian Journalist Vladimir Pozner. The reaction to the visit was used to further corroborate the existing narrative that Georgia is a Russophobic country, outlining that it is dangerous for Russian citizens to travel to Georgia.14

As noted above, Russophobia is not a new narrative and neither is it endemic to Georgia. This is confirmed by the EU’s review of disinformation regarding Russophobia.15 The data-set used by the EU contains 614 mentions of the word – “Russophobia”.16 The Russophobia narrative, inter alia, acts as a time bomb, with the goal to become embedded in the reader’s mind while activating it in a periodic manner.

The Lugar Laboratory and Biological Security

The first clear example of a premeditated and targeted attack on the biological security front came in the form of intensified disinformation regarding the Lugar laboratory, which was already under heavy pressure in terms of Russian hybrid warfare campaigns.17 This was before the Coronavirus pandemic. Starting from as early as January of 2020 Russian media sources published articles blaming the Lugar laboratory, and by default the US, for the development of the dangerous virus over a long period of time.18 This might be hinting at the fact that the manipulation of public consciousness takes place well before the initiation of actual planned events. This was confirmed as accusations towards the Lugar laboratory began to be voiced by the Russian authorities and officials not long afterwards. By October of 2020 the Press-speaker of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated the following during a briefing: Russia is concerned regarding the “US using the Lugar laboratory as a cover for its military and bio-medical activity”.19

Russia even attempted to rope China into this disinformation narrative. An official representative of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Geng Shuan, reminded the US of its laboratories located all over the former Soviet Union.20 Later, the Chinese Ambassador to Georgia, Li Yan, gave no comment to the Georgian media regarding the inaccurate interpretations of the Lugar laboratory issue in regard to Georgia.21

The Second Karabakh War and Regional Security

Another clear example of manipulation of public opinion manifested itself in the form of the Russian disinformation campaign over the Karabakh war, attempting to paint Georgia as a biased party to the conflict, despite Georgia’s adamant insistence on its neutrality. Prior to the initiation of military action, in August and early September, a new keyword/key phrase was identified: “Tensions in the South Caucasus”, which aimed to dislodge the foundations of the strategic relations between Georgia and Azerbaijan.22 Articles containing such content depicted Azerbaijan as Georgia’s enemy in the region. Later, this narrative was continued within the context of rising tensions over the Karabakh war and the wider anti-Turkish sentiment.23

It must be noted that in order to clearly outline how Russian disinformation lays the foundations for respective Russian foreign policy behavior, it is not enough to simply analyse Russian media. Furthermore, identification of Russian disinformation narratives acts as one of the most useful tools for the relatively accurate prediction of Russia’s complex foreign policy priorities. Therefore, in this regard it is desirable to continue working on increasing the number of analysed articles, as well as applying the random selection method.

Moreover, along with media analysis, it is necessary to qualitatively analyse Russia’s foreign policy, which entails the identification of long-term and short-term policies Russia exercises towards Georgia. Based on said analysis and in response to it, it would also be necessary to conduct strategic communications in response.

Long-term indicators include the violation of Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity on behalf of Russia. Similarly, Russia also refuses to accept Georgia’s pro-Western foreign policy. In this regard, Russia is a predictable actor. The goal of strategic communications would be to plan actions accordingly in order to maintain high public, as well as international support towards Georgia’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and the pro-Western foreign policy vector.

Short-term indicators include Russia’s immediate reactions to bilateral, as well as international political events that influence Georgia’s foreign policy objectives. Russia’s involvement and role in the Second Karabakh War may be the case in point, along with the rivalry between Russia and the West, and developments within the bilateral Russo-Georgian framework. In terms of responding to such current events it is the goal of strategic communications to clearly and timely identify and negate dominant Russian disinformation narratives both for the domestic as well as international audiences. This can be achieved via the means of conducting a facts-based, targeted and prolonged communications campaign.

Close inter-institutional coordination among various bodies is necessary for the mitigation of the negative effects of Russian disinformation narratives. Correctly employing strategic communications and selecting an institution responsible for countering harmful anti-Western disinformation campaigns are also vital. The strengthening communications capabilities of Georgia’s diplomatic missions abroad, as well as the Strategic Communications Department itself could be one of the helpful ways to that end.

It would also be beneficial to cooperate with the civil society organizations working on said topic. Effective communication and coordination will provide the state with the capability to assess its existing knowledge and available resources, in order to fully integrate its actions with foreign policy priorities of the Georgian state.

Finally, it would be necessary to strengthen communications with NATO, the EU member states, and the US, in order to coordinate processes and mobilize appropriate resources. Nevertheless, it must be noted that several important steps have already been taken in this regard. In 2020 Georgia joined the Global Engagement Centre’s (G.E.C.) the GEC-IQ platform, which serves the purpose of increasing resilience towards Russian propaganda and disinformation campaigns.

It can be said that Russian disinformation acts as a foundation for Russia’s foreign policy. Therefore, bringing the aforementioned disinformation narratives to light can be employed as a useful tool in terms of predicting Russia’s actions. For this purpose it would be preferred to further solidify the existing approach, which entails both the qualitative and quantitative analysis of Russian disinformation narratives, as well as the strengthening of the institutional foundations of the Georgian state responsible for combatting anti-Western disinformation and propaganda. This includes tight coordination with local civil society organizations, the scientific community, as well as international partners.

* Mariam Orjonikidze – Attaché, Department of Strategic Communications, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia

Contents

Georgia’s European Path From Declared Aspirations of Membership to Official Accession Goal

Eka Pkhovelishvili

Russian Disinformation Campaigns and the Role of Strategic Communications in Planning Successful Foreign Policy

Mariam Orjonikidze

NATO 2030 New Vision and Eastern Expansion Policy

Rati Asatiani